Human Rights Activist And Independent Researcher, Norway

By Zu Anjalika Kamis Gunnulfsen

Seyran, before we get started on the questions about Iran, it will be great to get to know you.

Thank you for having me!

My name is Seyran Khalili and I am a Kurdish-Norwegian human rights activist and independent researcher based in Norway. Currently, I work on the subject of feminist leadership and meaningful participation in New Women Connectors, a movement for leading and nurturing resilience that brings the unheard voices of migrants and refugee women living across Europe into the mainstream.

I was born in Kurdistan province of Iran. I have been based in Norway since early childhood, relocating to Norway with my family as a political refugee. As an organisational psychologist, I hold a master’s degree in psychology and have specialised in city development and prevention work in recent years. For more than 12 years I have been actively involved and engaged with a commitment to developing better dialogue amongst civil society, migrant communities, refugees and women-led initiatives.

My two focus areas have been women’s rights, migration and integration policies.

Over the past decade, I have been working with advocacy with great commitment to advocate for issues of social injustice, reducing the gap between minorities and the majority through dialogue, information, and community debates. My profession occurs within a matrix of theory-based innovations in public service, leadership development, and cross-cultural communication. Lately, my interest has been focused on using service design and innovation processes for city development, particularly emphasising the meaningful participation of citizens. I have served as a deputy Board member of the Norwegian NGO “LIM – Equality, Inclusion and Diversity” since February 2017. I am also an associate of Kings College London through completing their Associateship (AKC), studying theology and philosophy of religion. As a young change-maker, I got selected to be a youth ambassador at the Università Della Svizzera Italiana through the Middle East Mediterranean Summer Summit 2021. I am a member of the GERIS (Global Exchange on Religion in Society) network and am well-grounded in advocacy work in an EU and global context. I aspire to make a difference in future generations’ lives through my advocacy work within civil society that can significantly impact people around them. Especially to work for causes that make this world a better place to live and thrive.

We are here to talk about the unfortunate circumstance in Iran. Sadly, the Iranians are no strangers to hard times – basic human rights is none existent in Iran for as long as we know. The suppression, oppression and brutality have been going on for more than four decades. Give us a little background on that.

In recent months, thousands of women and men have taken to the streets of Iran. Headdresses are burned, and clergy are ridiculed. Videos on social media show young Iranians tearing the turbans off clerics in the streets.

It has never happened before and frightens the regime, which now wants to introduce the death penalty against protesters.

The protests in the wake of the murder of Zhina Mahsa Amini (22) join the series of extensive protests against the clerical rule in Iran ever since the revolution in 1979 when over 100,000 women demonstrated against the mandate for head coverings. Other protests, such as those in 2019 and in 2020, lasted for several months.

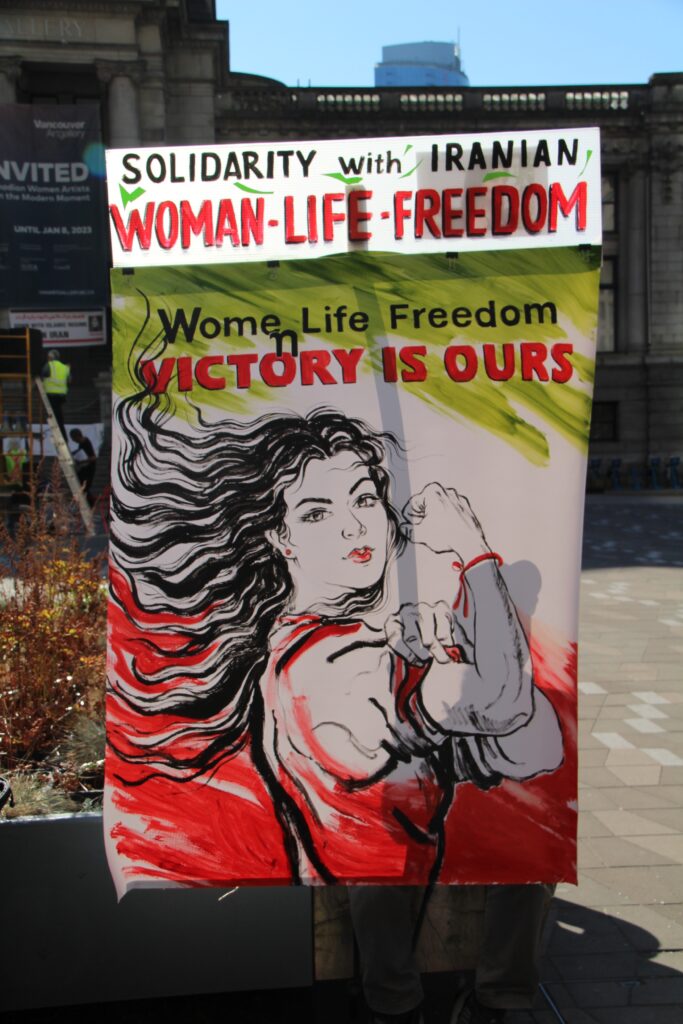

The regime has survived repeated and prolonged waves of protest and several decades of tough sanctions. The demonstrations following the death are the largest since the start of the Islamic Republic in 1979 and are seen as a major challenge to the regime. They call the uprising a Women’s Revolution, and use the slogan “Women – Life – Freedom”. After the murder of Mahsa Amini, whose name was Zhina in Kurdish, the originally Kurdish slogan became unifying. Feminism in Iran has long historical roots. During the revolution against the shah regime in 1979, many women were active, without calling themselves, feminists. Seeing the direction of the new regime, many women became nervous.

On March 8, 1979, after the Islamic Republic was established, hundreds of thousands of women demonstrated against plans to require them to wear the hijab. They lost that match. Afterwards, there have been periods where women have strengthened their positions, gained a greater place in working life, and where there have been more elected reformists. But since 2009, many have completely lost hope for reform.

Many young people have lost faith in the future. The years-long sanctions against Iran mean that many cannot travel abroad to study or work, as they are denied visas. The corona pandemic hit hard, the economy is in crisis, the regime closes the internet, and they see increased financial differences, corruption, powerful regime people – many feel they have nothing more to lose.

The world is no stranger either to the happenings in Iran. However, it is only very recently we have taken more notice of them. The Mahsa Amini case has angered the world. A young woman was taken in because she wasn’t adorning the hijab “correctly”. Next thing we know she died while in police custody. How common are these types of cases in Iran?

Iran’s so-called “morality police” are tasked with ensuring respect for Islamic morality as described by the country’s clerical authorities. Among other things, they involve reporting on “bad hijab”, a collective term that applies to violations of the country’s strict dress code for women. Under Sharia law, women are required to cover their hair and wear long, loose-fitting clothing to hide their figures. A typical morality police unit consists of a van, one man and one woman, which patrols or waits in busy public spaces to monitor improper behaviour and dress. People who are apprehended by the morality police either get away with a warning or are taken into custody at a police station or a detention center, where they are told how to dress or behave “morally”. Women are released only to male relatives. In some cases, fines are also given, although there is no general rule on monetary penalties. The moral police are officially known in Iran as Gasht-e Ershad or the “guidance patrol”. There have been demonstrations against Iran’s strict dress code for women since the Iranian revolution in 1979.

Established in 2006, the police force is called Gasht-e Ershad, which can be translated as the “guidance patrol” and was formally established by then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2006.

The “special police force” was supposed to ensure modesty and decent behaviour among the country’s citizens and ensure that Iranian women adhere to the dress codes set by the country’s religious leaders.

Islamic Sharia law states that women are obliged to cover their hair and wear long, loose-fitting clothes to hide their figures. In Iran, it was legislated that women must wear head coverings to hide their hair in 1983.

Ever since the ban came in 1983, Iranian women have deliberately pushed their boundaries. A common sight in the bigger cities is to see women in tight jeans and colourful scarves hanging loosely over their heads and shoulders. The scarf is well pulled away from the forehead so that much of the hair is still visible. Unmarried men and women who are not related may not walk or sit together in public.

Children are also not spared by this regime. To date (end of November 2022), 58 children have been reportedly killed since the anti-regime protests started on September 16. Talk to us about that, Seyran.

The country has gained several young demonstrators and several young symbols. They are met with inhumane violence. There are children who have been shot in the head, shot in the heart, and beaten all over with clubs. So the protests spread, but so does the completely insane violence that the Iranian authorities meet them with.

These young protesters mostly belong to Generation Z, i.e. those born between 1997 and 2012.

The parents and grandparents of this generation also protested in their time but were unable to bring down the regime then. Now, at a time when the vast majority of young people are present on social media such as TikTok and Instagram, and several of those killed have posted videos on social media, the protests have also spread like never before.

I would like to add that this is not about religion or Islam. This is only about removing the Islamic regime. It’s not about the hijab, but about the freedom to choose to put it on – or take it off. It’s about stopping giving men power over women’s bodies.

Tell us a bit more about the government’s decision to shut down the internet.

Throughout the protests over the past three months, the Iranian authorities have been trying to shut down internet access to control the action narrative. The authorities in Iran claim that the protests are not about women’s rights. On the contrary, they claim that it is enemies of the country who are orchestrating the demonstrations to smear them.

At this point what kind of help are Iranians getting from the world?

Countries worldwide consider how to help protesters in Iran. At the beginning of November, the Security Council held a ground-breaking meeting on the demonstrations in Iran. Now the UN Human Rights Council will investigate whether the authorities in Iran’s actions against protesters are a violation of international law.

The Human Rights Council will now uncover human rights violations in Iran. The Council is the UN’s highest body in human rights matters. They work to ensure that human rights are safeguarded and are responsible for dealing with situations where they are violated. Excessive use of force, repression and persecution of demonstrators are violations of international law. In an extraordinary meeting, a majority of the council’s 47 member states voted in favour of the proposal to send a team to start the investigation of human rights violations. The resolution was adopted with 25 votes in favour, 6 against and 16 abstentions. It’s a simple step but an important one.

As things stand today, there’s no accountability for the crimes being committed in Iran. The country’s authorities refuse to even investigate their own abuses, obviously, let alone hold anyone responsible for them.

Several countries from the EU and the US have imposed new sanctions against the authorities in Iran because of their brutality in the face of peaceful protesters. The US has also announced that it is continuing to work with other actors to remove Iran from the UN Women’s Commission.

How can we help from the distance?

A united international community now shows support for the Iranian people and has indicated increased sanctions against the regime. Trade with the Iranian regime should be conditional on respect for human rights and the release of all political prisoners. The good news is that everyone can contribute to this work.

You can send an email to your country’s foreign minister.

Iranians want democracy, equality between the sexes and to live in peace with the outside world, everyone should help ensure that – including the international community!

Any last words, Seyran?

I would like to add that this is not about religion or Islam. This is only about removing the Islamic regime. It’s not about the hijab, but about the freedom to choose to put it on – or take it off. It’s about stopping giving men power over women’s bodies.

This fight is not an open invitation to suppress religion or tell women that now is the time to take off the hijab. Some Muslim countries force women to wear the hijab, while in Western culture, choosing your own clothing is a symbol of freedom. The problem is not the hijab, but the fundamentalist mindset often practised by men who have allowed themselves to rule over women and their bodies.

The important fact is also to take into consideration the intersectionality of discrimination. There have been 43 years of oppression in Iran. To this day, a system of gender apartheid and ethnic oppression is maintained. The Kurdish woman Zhina Amini, known as Mahsa, was been killed by the Iranian moral police because she did not cover her hair sufficiently, but her life was also extra exposed on the basis that she was Kurdish and this unpleasant but important detail we must dare to include in the news picture. It is important to include this in the debate because we know that minority women, even in democratic countries, are more exposed to discrimination and neglect than majority women.

They need us in the West to show that we care and raise our voices for them – a voice that has been taken from them for decades.

As a feminist, I want my fellow sisters to show solidarity and be their voice.

Jin-Jyan-Azadi

Zan-Zendegi-Azadi

Women-Life-Freedom